A few weeks ago, I had the honor of presenting to Golden Seeds, one of the largest angel groups in the US (and arguably the largest focused on investing in women-led businesses), on climate tech.

I was struggling a bit with figuring out a topic until I started thinking about the role of angel investing in climate tech.

In normal angel investing, angels come in as gap fillers - bridging (figuratively but sometimes literally) friends and family money and VC capital. Traditional angel investing prep founders for the first institutional VC round, which means angel investors primarily look for investments that are VC-worthy. A quick search for angel investing how-to's (AngelList's resource center, SeedInvest's Angel Investing 101, FasterCapital's Comprehensive Guide to Angel Investing) reveals that angel investing is pretty much synonymous with investing in early stage startups and is often discussed in the context of venture capital.

In climate tech, this paradigm doesn't work quite as well. Many businesses are what I would call non-venture models. These include "developer" businesses and new service providers...some examples in the presentation below. These businesses have different, often slower growth trajectories but can get to cash flow quicker. They also don't necessarily need a VC in the next round.

When it comes to angel investing in climate tech, I wondered if there were more creative ways in which angels could make an impact outside of copying the same model as in traditional angel investing. My three suggestions:

- Invest more in climate tech and invest intentionally in underrepresented technologies - as shown in data from the Angel Capital Association, there is still room to allocate more capital to climate tech from the overall pool of angel capital available. And within climate tech angel investing, capital tends to stay away from industrial and energy, sectors that, on an emissions basis, have a disproportionally larger impact than others. So angels can think about investing more intentionally into areas that have bigger emissions impacts.

- Be open to funding early stage non-venture models using a "micro-private equity" mindset, examining time to cash flow, collateralization, and using more structured convertible debt - this is one that is probably hardest to give a good recommendation on because these growth models are still being developed. But for early stage businesses in climate tech that aren't traditional venture models and don't have "unicorn" potential, perhaps there's some form of micro-private equity angel investing that can fill a gap between non-cash flow and cash flow stages of a business. These businesses may still not be able to access traditional small business lending but still have a need to fund operations for a small business model. So is there a way for angels to write creative paper, like tranched convertible debt with a tailed coupon and some collateralization, in order to fund these businesses?

- Be carbon champions in the community by early adopting new consumer-facing technologies - finally, angels also tend to be relatively wealthy & impact-oriented individuals compared to the general population. Like how the early buyers of higher-end Tesla models eventually supported the mass commercialization of the business, can angels become early adopters of certain technologies in order to support their commercialization into the mainstream?

As I prefaced while delivering this live, I am new to angel investing myself so would love to foster more of a discussion on these suggestions vs. being overly prescriptive. Especially on #2 since it involves templating a new financial instrument.

See the presentation below. Would love feedback from and to start a discussion with any angel investors out there that are reading this!

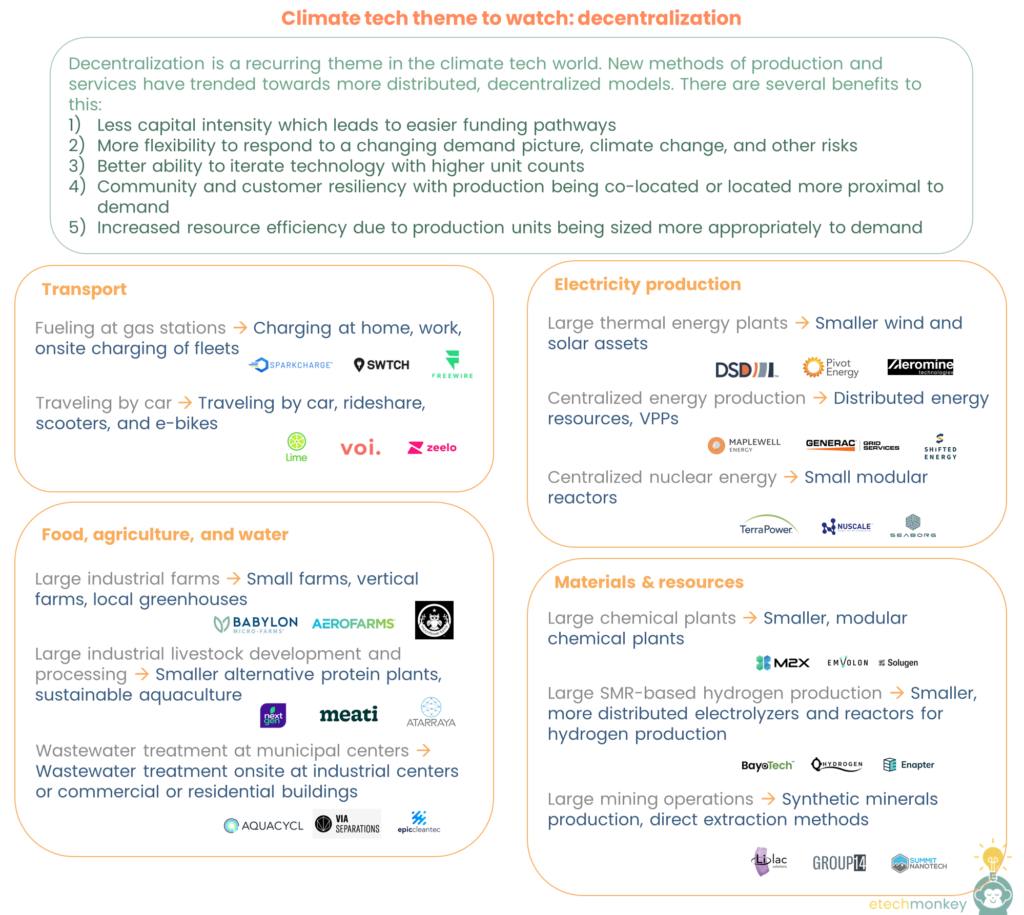

I’ve been looking how we might be able to create a financial ecosystem tailored to growing and scaling climate tech and what themes might impact that kind of financial ecosystem. One of these themes is this concept of decentralization.

Many different climate tech sectors rely on decentralized models of producing goods and services, following a broader industrial trend of localizing manufacturing and reshoring industrial facilities. While this goes against the traditional paradigm of centralizing everything to achieve optimal economies of scale, there are clear benefits to following a decentralized model:

- Less capital intensity - one of the biggest advantages of decentralized models is that they require less capital to get started. Traditionally, large, centralized production facilities have required huge amounts of investment to set up, which can be a barrier for many entrepreneurs and startups. Decentralization, on the other hand, enables smaller-scale, distributed production, which can be achieved with lower capital investments. This leads to easier funding pathways, as it allows for more entrepreneurs to enter the market and compete.

- More flexibility - decentralized models also offer more flexibility to respond to a changing demand picture, climate change, and other risks. Large, centralized facilities can be difficult to adapt and retool quickly, whereas smaller, more distributed production units can be more nimble and responsive to changes in demand or new environmental threats. This can lead to a more efficient use of resources and less waste.

- Better ability to iterate technology - decentralized models also have a better ability to iterate technology with higher unit counts. Smaller-scale production units can be designed and built more quickly, enabling more iterations to be tested in a shorter amount of time. This can lead to faster innovation and more efficient technology development, which can ultimately help address the climate crisis more effectively.

- Community and customer resiliency - decentralization also enables community and customer resiliency, as production is co-located or located more proximal to demand. This can help mitigate the risks associated with supply chain disruptions or natural disasters, which can have a significant impact on traditional centralized production facilities. By spreading production across a wider geographic area, decentralized models can help ensure that essential goods and services are available to local communities even in the event of a disruption.

- Increased resource efficiency - decentralized models can lead to increased resource efficiency due to production units being sized more appropriately to demand. Traditional centralized facilities often produce goods in large quantities, which can lead to waste if demand is not met. Decentralization enables smaller, more appropriately sized production units, which can help reduce waste and improve overall efficiency.

On specifically the finance front, decentralization can be an alleviating trend to climate tech’s FOAK problems. As more project sponsors and offtakers buy into building infrastructure for new decentralized paradigms vs. building infrastructure for old centralized paradigms, we may be able to use the VC growth model to scale up more of climate tech.

In the past, my posts have focused on how finance can adapt to scale up climate tech and how scaling climate tech is a uniquely challenging problem…but diving into themes like this is a good reminder that 1) the problem is evolving and 2) that the “compromise” doesn’t necessarily have to be completely from the finance side…perhaps technology can evolve to be more fitting to our financial ecosystem.

I see 11 areas in climate tech clearly embodying the decentralization theme (though I’m sure there are more!):

- Fueling at gas stations ⟶ Charging at home, work, onsite charging of fleets

- Example companies: SparkCharge, Swtch, Freewire

- Traveling by car ⟶ Traveling by car, rideshare, scooters, and e-bikes

- Large industrial farms ⟶ Small farms, vertical farms, local greenhouses

- Example companies: Babylon, Aerofarms, Moonflower Farms

- Large industrial livestock development and processing ⟶ Smaller alternative protein plants, sustainable aquaculture

- Wastewater treatment at municipal centers ⟶ Wastewater treatment onsite at industrial centers or commercial or residential buildings

- Example companies: Aquacycl, Via Separations, Epic Cleantec

- Large thermal energy plants ⟶ Smaller wind and solar assets

- Example companies: DSD Renewables, Pivot Energy, Aeromine

- Centralized energy production ⟶ Distributed energy resources, VPPs

- Example companies: Maplewell Energy, Generac Grid Services, Shifted Energy

- Centralized nuclear energy ⟶ Small modular reactors

- Example companies: TerraPower, NuScale, Seaborg

- Large chemical plants ⟶ Smaller, modular chemical plants

- Example companies: M2X Energy, Emvolon, Solugen

- Large SMR-based hydrogen production ⟶ Smaller, more distributed electrolyzers and reactors for hydrogen production

- Example companies: Bayotech, Q Hydrogen, Enapter

- Large mining operations ⟶ Synthetic minerals production, direct extraction methods

- Example companies: Lilac Solutions, Group14, Summit Nanotech

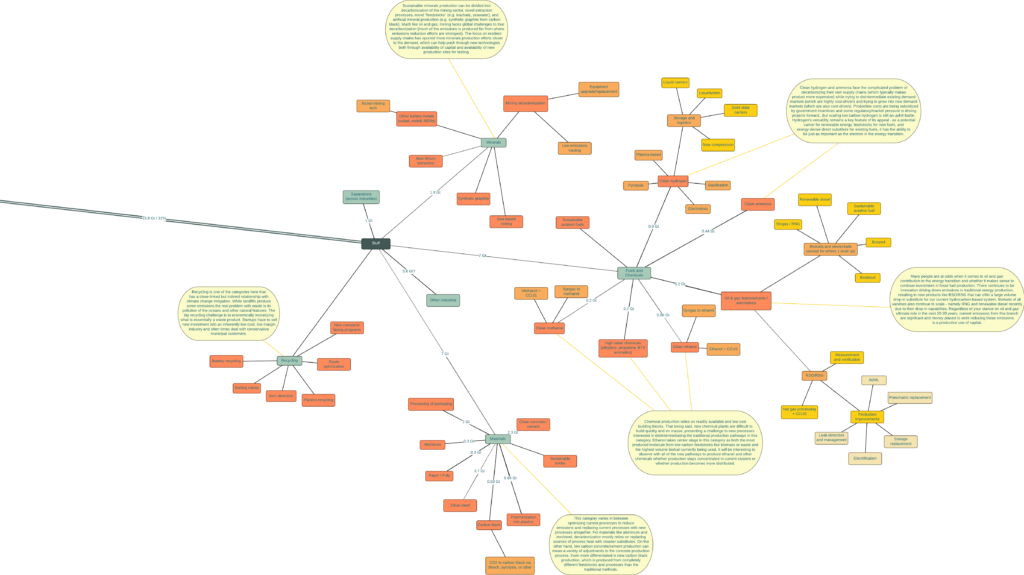

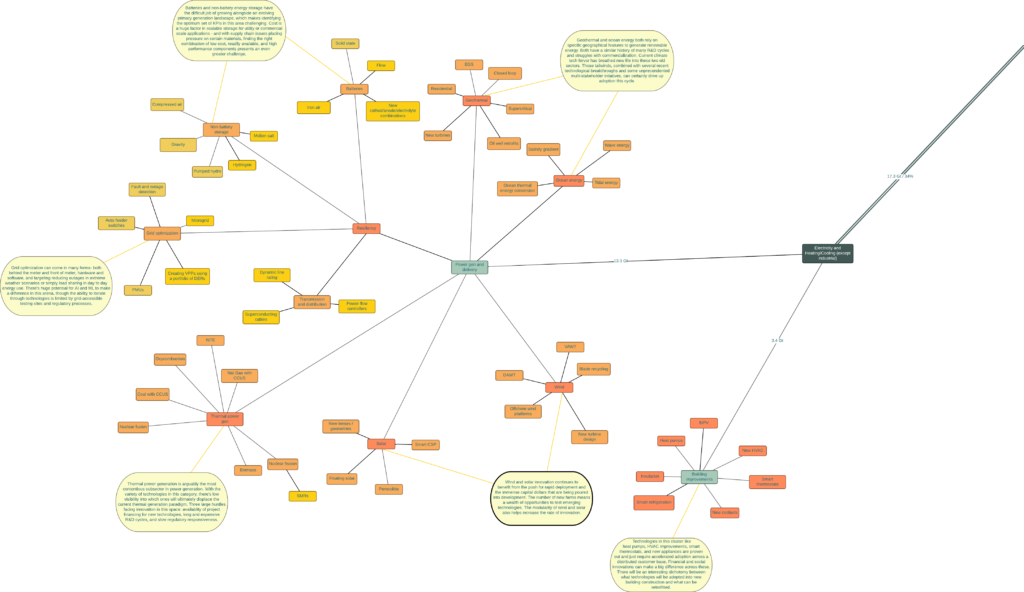

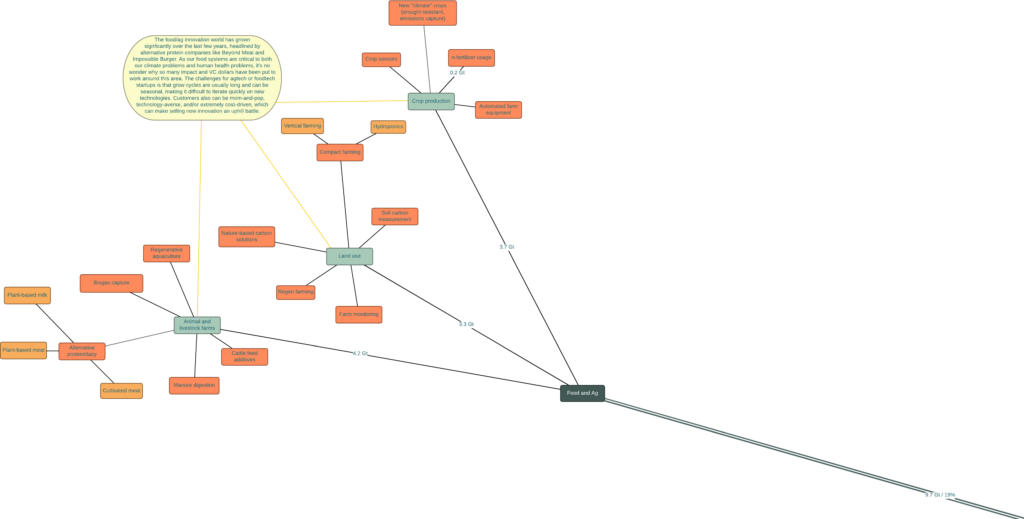

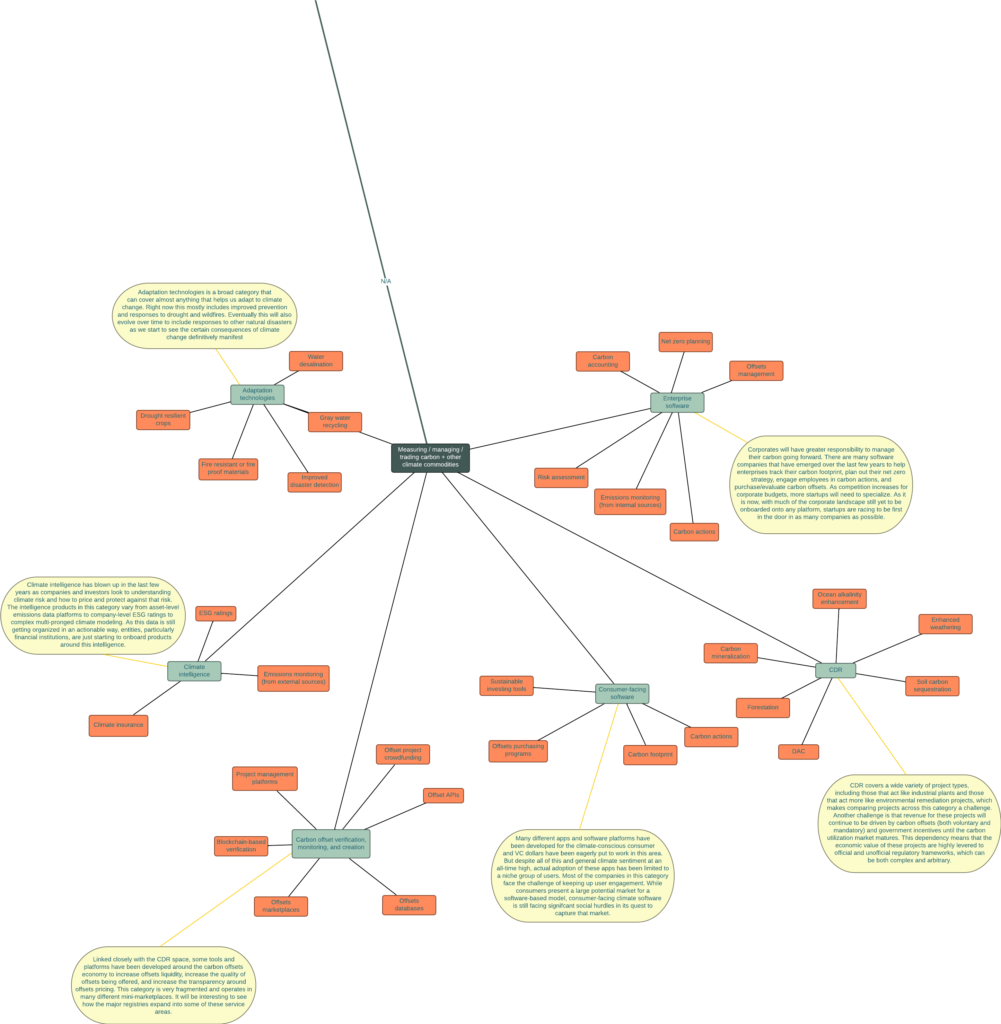

I thought it would be a good "New Year" exercise to update the FEST map and add some thoughts on each climate tech sector.

As a reminder, FEST is a framework, inspired by Bill Gates' book, that illustrates the impact of climate tech on the different parts of how we live. Emissions can broadly be divided into Food (F), Energy (E), Stuff (S), and Transport (T).

I use this chart as a reference for looking at the different climate technologies in the context of the broader picture. It's by no means comprehensive...at least not yet! This current version has ~170 nodes, with each node representing a niche of climate technologies.

Updating this has generated some interesting ideas for me of what to write about this year. I hope it's as helpful for you as it is for me.

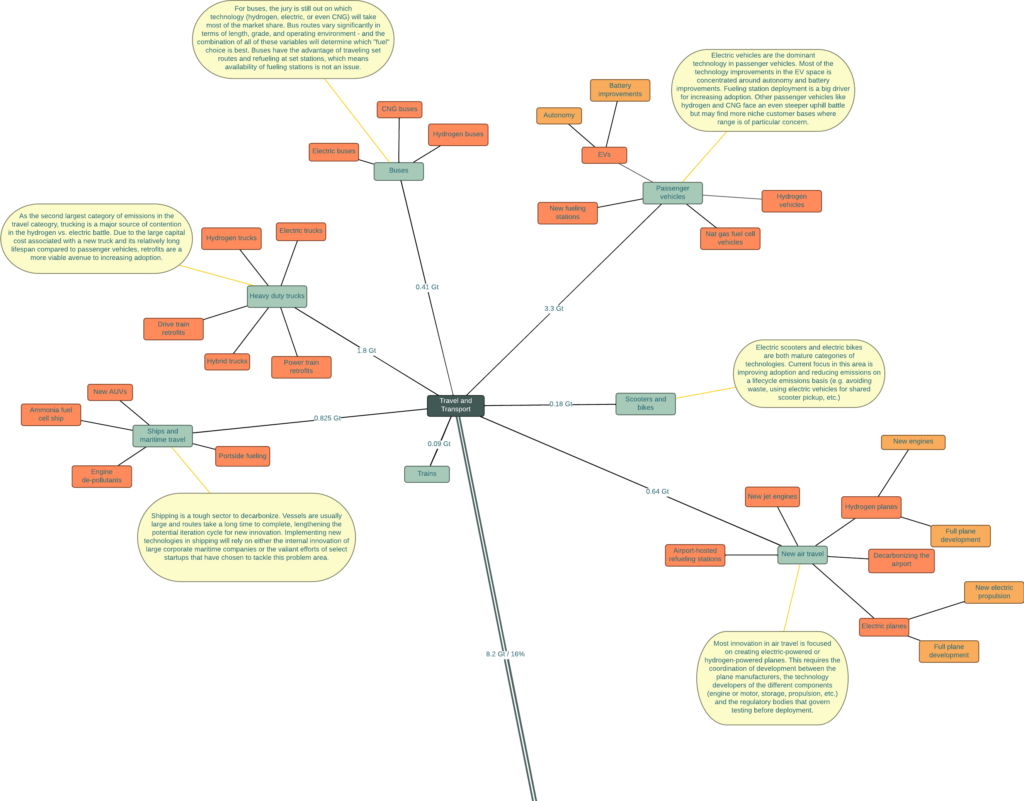

Transport

Ag/Food

Happy New Year!

I spent some time over the holidays making a fun little reference timeline for the IRA credits. The various effective dates can be confusing and I figure it would be helpful to have a birds eye view of when each provision comes into play.

From this angle, we can observe that there are several critical deadlines in which a good chunk of the new IRA credits come into effect or go out of effect: the beginning of this year, 1/1/2023, 1/1/2025, and 1/1/2033.

There are still certain provisions that rely on federal guidance before they are in effect, something that can affect actual deadlines. For example, the guidance for the critical minerals and components requirements for clean vehicles was supposed to be issued by 12/31/2022. Due to a delay in the guidance until March 2023, certain vehicles that qualify for the credit without taking this requirement into consideration can now qualify for the credit until the guidance is issued (like Tesla).

Check out the pdf or spreadsheet versions below and as always, let me know if you have any feedback.

Full tax code with the IRA adjustments available from Tax Notes

Past IRA analysis / summaries:

- Clean Vehicle Credit analysis: https://etechmonkey.com/index.php/2022/08/18/you-dont-get-a-credit-and-you-dont-get-a-credit-the-impact-of-iras-new-clean-vehicle-credit/

- Methane fee analysis: https://etechmonkey.com/index.php/2022/08/11/the-iras-methane-reduction-program-is-a-gentle-push-in-the-right-direction/

- IRA Credits Summary: https://etechmonkey.com/index.php/2022/08/04/latest-beach-read-the-inflation-reduction-act/

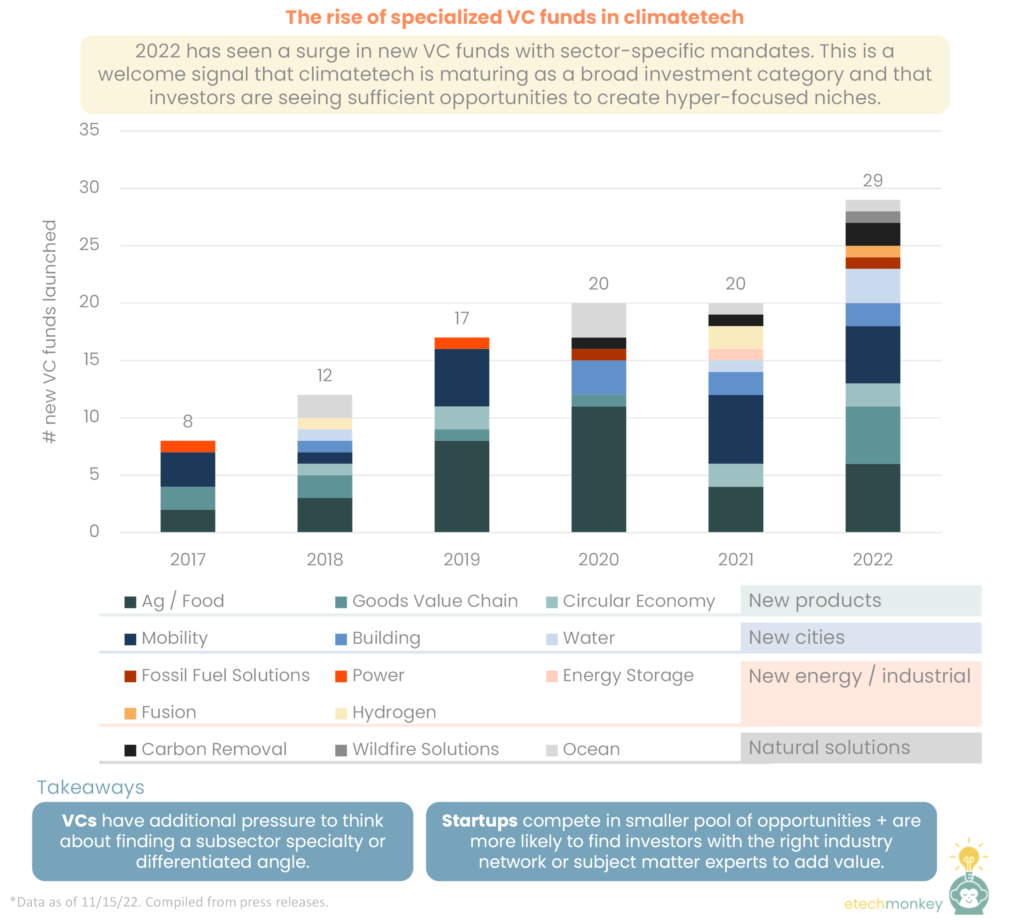

There’s been a LOT of money poured into climatetech over the last few years and even with the recent downturn, new money keeps coming in. According to CTVC, 2022 has seen an uptick in the number of new climatetech VC investors announced (45 -> 47), despite rising interest rates and a broader market slowdown for VC. It seems that the LPs of the world – endowments, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, mega-family offices – are still quite bullish on climate and hungry for new early stage funds in this space. And as climatetech deal activity (as measured by deal count) also hasn’t slowed, new fund managers continue to have opportunities to deploy capital in.

So the environment for being an investor in climatetech seems to be as good as ever these days…but has it evolved at all in other ways? That’s the question I was asking myself after I read this update. I suspected that the VCs that are raising money today in climatetech are of a slightly different flavor than the VCs raising money in climatetech a few years ago.

Examining the climatetech-oriented or related funds that have been raised over the last 6 years, I found that there’s been an interesting evolution that’s been happening when it comes to sector specialization. While most of the funds raised in the early days of climatetech / cleantech were generalist in nature, recent funds seem to have erred to choosing specific niches within climatetech like alternative proteins, buildings, or circular economy.

A taste of some of the announcements this year:

- Lowercarbon Capital’s $250mm fusion fund and $350mm carbon removal fund

- Propeller’s $100mm fund for ocean-related climate technologies

- Energy Capital Ventures’ $61mm fund for greening the natural gas industry

- Emerald’s $217mm sustainable packaging fund

- Convective Capital’s $35mm fund for wildfire solutions

- Capricorn’s $26mm industrial biotech for cleantech fund

- Burnt Island Ventures’ $30mm water fund

A total of 29 specialist climate funds have been launched this year, up 45% from last year. That’s out of a total of 106 specialist climate funds that are actively investing. These 106 funds span 14 specialties which can be aggregated into 4 main categories. All of this is shown in the chart below.

Some observations:

- Early specialist funds were concentrated on new ag/food and mobility. In the last two years, specialist funds cover a more diverse set of specialties.

- These funds don’t necessarily have to be completely new funds. 11% of these new specialist funds come from existing VCs with a more generalist or broader focus.

- This dataset only shows institutional specialist funds. Other specialist funds naturally exist through corporate venture capital, where strategics typically aim to invest in specialties that can complement or overlap with their existing business. Having more institutional specialist funds blurs the line a bit between the value add from a CVC and the value add from a VC, creating competitive pressure for the CVCs to add outsized strategic value or offer better terms in a transaction.

Overall, specialization is a positive development for the climatetech world. It’s at the very least a signal that climatetech is maturing as an investment category and fund managers are getting more sophisticated. It’s also a good sign that investors are seeing ample opportunities in climatetech for the long term.

The consequences of specialization are net positive. Having more specialized VCs places additional pressure on other VCs to think about finding a differentiated angle to offer to startups. This can push the investor world to developing better, more value-added relationships with their investments. For startups, having more options from specialist VCs increases competition in their favor, while taking money from specialist VCs can offer more strategic channels to the right industry network.

The other side of specialization is that specialist funds have limited options when it comes to pivoting in a challenging macro environment, leaving them vulnerable to industry-level macro shifts. Choosing to specialize is taking a risk that your chosen specialty will be around for years to come. Having an increasing proportion of specialist VCs in the climatetech ecosystem means that the overall capital stack for climatetech has more points of vulnerability.

But all in all, there are benefits of specialization to both the investors and startups.

For investors, specializing allows for:

- Easier deal screening. Less deals need to be vetted in a smaller market, allowing for more time to be spent with fewer companies. Having a public sector-specific mandate also means startups working in that area are more likely to know about you and proactively reach out.

- More thoughtful deal screening. Certain sectors may have sector-specific metrics that may be more relevant than traditional VC metrics like revenue or EBITDA. Things like quality of patents, technical benchmarks, partnership agreements, customer indications, etc. can be assessed in more depth in deal screening. For many VCs, especially ones coming in from tech to climatetech, using criteria that is too generalist may exclude startups that are expressing momentum in other ways.

- More leverage in attracting “hot” startups. In competitive, oversubscribed rounds, investors with clear differentiation and strategic value often have more appeal to startups than other investors, even those with more favorable valuation/terms. Similarly, a niche focus can help investors without a substantial track record argue their value to startups.

- Portfolio synergies. Investors that specialize are better able to aggregate resources particular to that specialty, like technical help, advisors, corporate partners, customer relationships, etc., for the broader portfolio, allowing startups in that portfolio to access those resources at lower cost. A specialized portfolio that brings together companies working around the same sector can also potentially find ways for companies in the portfolio to work together, officially or unofficially.

For startups, specialist funds can allow for:

- Easier investor screening. Most capital raises involve conversations with a hundred or so investors, with half of those being immediate dead ends because of lack of transparency by the investor on what problem areas they are interested in. Specialist VCs are very clear on this aspect, allowing startups to schedule those conversations without fear that time will be significantly wasted.

- Reduced competition with deals in other industries. Pitching to a generalist fund or a fund with a broad climate mandate can mean that your startup is being compared to other startups that have a totally different growth model. Investing in a materials science company selling into the auto market is worlds apart from investing in a carbon credit software company selling to consumers. Evaluating these deals together often time favors a certain industry or growth model instead of favoring the better company.

- More value-added partnerships. Specialist VCs often have more relationships within industry, which means that startups that partner with specialist VCs can access more relevant resources that can help them scale. Specialist VCs are likely also better able to contribute meaningfully to accelerating the startup’s growth as board members or advisors, making them better partners in the long run.

- Easier access to subject matter experts. Specialist VCs attract other specialist service providers and specialist partners, which means taking on a specialist VC can naturally allow a startup access to a wide array of subject matter experts in their sector. This can make the build process on a niche problem a lot less painful.

TLDR; we’re seeing more specialist VCs in climatetech. And that’s a good thing for the ecosystem.

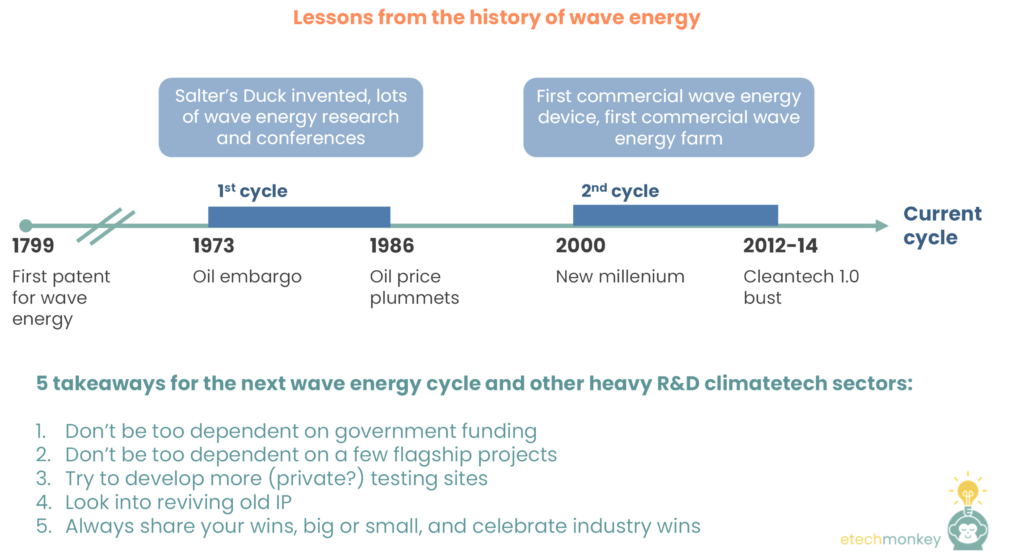

Last time I looked at the history of wave energy and what lessons we can draw from past cycles that could be relevant to today’s climatetech challenges.

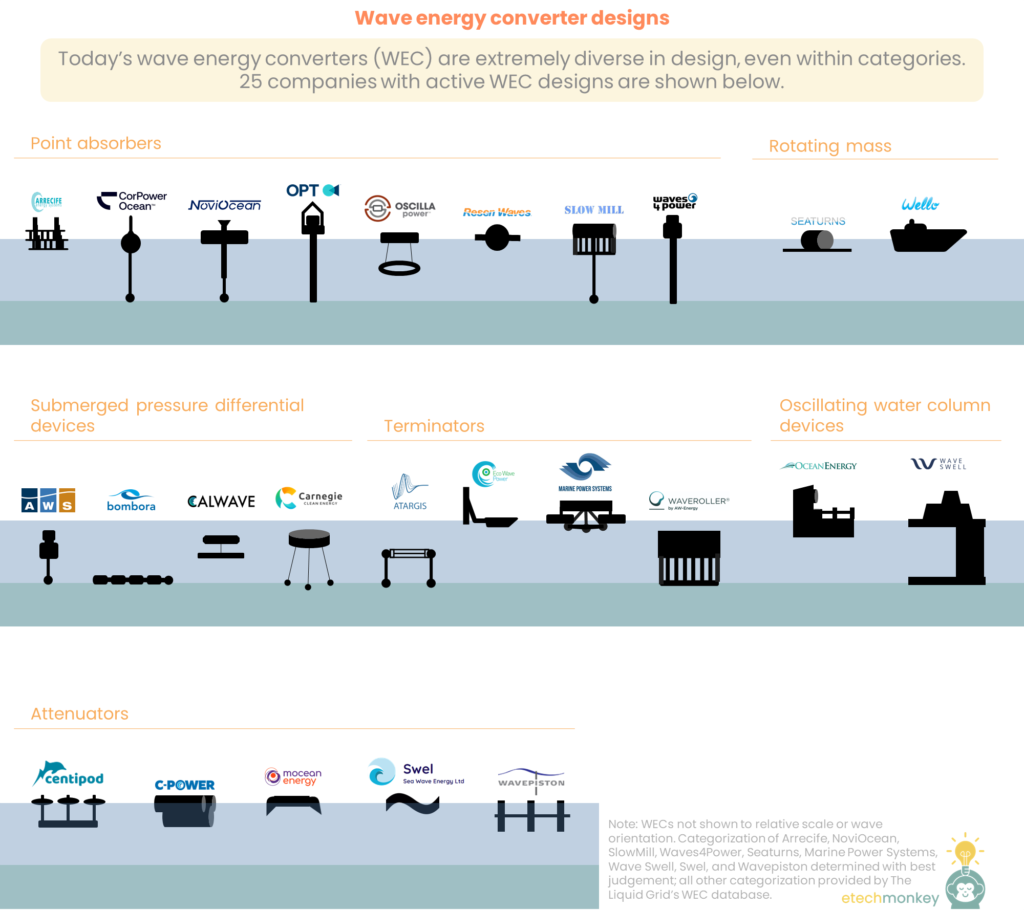

This week I wanted to create the actual wave energy market map, in part to get a better sense of the variety of wave energy converters (WEC) that are being developed today and in part to better know and appreciate all of the companies that are working in such a difficult but rewarding space.

Though there have been hundreds of WEC designs proposed in the last few decades (130+ are included in The Liquid Grid’s database and 94 in Net Zero Insights' database), only a small fraction of those are still being developed today. I found 25 that are actively on the path towards commercialization (loosely defined to be: 1- not just a project by an academic institution and 2- having at least one announced milestone in the last year). Those 25 land in six different WEC categories that I could identify.

Included in this map:

- Point adsorbers (or absorbers in some literature) are WECs that float at the surface like a buoy and can be attached to the seabed. They usually, but not always, can capture wave movement from multiple angles. Many translate the movement to vertical pumps on the seabed. Companies creating point adsorber devices include Arrecife, CorPower Ocean, NoviOcean, OPT, Oscilla Power, Resen Waves, Slow Mill, and Waves4Power

- Related, but not quite the same, are rotating mass WECs. Rotating mass WECs also float at the surface but use an internal rotating weigh to generate electricity. Companies with rotating mass WECs include Seaturns and Wello

- Submerged pressure differential devices are under the surface and use pressure fluctuations from the overhead waves to generate electricity. Like point adsorbers, they can be fixed to the seabed. Companies with submerged pressure differential WECs are AWS Ocean Energy, Bombora, Calwave, and Carnegie Clean Energy

- Terminators are a broad set of WECs that specifically orient perpendicular to the direction of the waves (in a “come at me” kind of way) and in doing so, terminate the waves. They are often fixed to a point like the seabed, shore, or an offshore platform. Terminators are very loosely defined and can include other oft-mentioned WEC categories like oscillating wave surge or oscillating water column. For the purposes of this landscape, I’ve separated out oscillating water column but not oscillating wave surge due to design similarities between the oscillating wave surge and other terminator devices shown. Companies that have terminator WECs include Atargis, Eco Wave, Marine Power Systems, and AW-Energy

- Oscillating water column devices are a class of terminators that uses the wave to raise and lower water levels within a column, which then forces air to go in and out of a turbine. Companies creating oscillating water column devices include OceanEnergy and Wave Swell

- Attenuators are WECs with segmented parts oriented along the direction of the wave. The relative movement of the segmented parts generate electricity. Attenuator companies include Centipod, C-Power, Mocean Energy, Sea Wave Energy, and Wavepiston

A few observations on this set:

- As expected, WEC designs are all over the place. The designs can be very different from one another, a factor of the many variables that you have to optimize for in wave energy (efficiency, resiliency, simplicity, maintenance costs, biofouling / corrosion risk, etc.). There are different angles targeted (against the wave, with the wave, pitch, roll, yaw, etc.), different depths operated, different mooring systems, and different turbines used. Even point adsorbers, the category which seems to have the most uniformity, are divided between seabed-fixed vs. free-floating designs.

- The heterogeneity makes it difficult to understand the value prop of each design. We often talk in the startup world about the need to highlight company differentiation…characteristics that make your company’s technology unique relative to your competitors. The problem with the wave energy space is that it’s too differentiated. The lack of standardization makes it hard to understand exactly what is critical differentiation and what is superfluous differentiation. In a population where everyone is super unique and different, no one can really stand out. For an investor that is not knowledgeable around wave, the many degrees of freedom around the design can be intimidating and discourage investment.

- Because of the wide variety in WEC design, metrics matter. It’s difficult to observe from the get-go how different WECs stack up against each other just based on design. But if the companies are upfront in publishing target metrics – LCOE, capital cost, maintenance costs, operating parameters, scalability — that can allow for easier benchmarking between companies, which can address the degrees of freedom problem for an investor in this space. It can also allow for easier pro/con discussions, which can help solidify which technologies are fit for which environments/situations.

Much of this benchmarking effort is underway in other climatetech sectors (carbon intensity and $/kg in hydrogen, LCOS in storage, tons avoided in carbon removal, etc.) but in wave, at least to an outsider looking in, there hasn't been as much of a concerted effort. In being more transparent around metrics, I believe the wave energy industry as a whole can invite more investment.

It's also worth noting that I made some purposeful exclusions in this landscape.

- I excluded businesses that combined their WEC design with a specific use case. Ocean Oasis and Oneka Water are using wave energy for desalination, E-Wave is developing WEC systems for aquaculture, and Ocean Motion is developing its WEC for ocean observation buoys. These are worth noting but because of their focused markets, I didn’t think they should be compared to companies harvesting wave energy for general electricity.

- A portion of ocean energy to be harvested includes non-wave kinetic energy from currents and tides. Companies like Current Power Energy Solutions are targeting ocean currents while companies like Nova Innovation are targeting tides. These are worth their own deep dive at some point.

After looking at the breadth of ocean-based climate solutions last week and having a better understanding around the potential of the ocean, I thought it might be informative to look at wave energy more specifically.

Four things that are worth noting about the wave energy space:

- The resource is huge. As mentioned last week, wave energy has the potential to be a critical asset for clean power generation. Wave energy alone can fulfill 67% of current US electricity demand (2,640 TWh / 3,930 TWh) and 140% of current world electricity demand (32,000 TWh / 22,848 TWh). By 2050, those numbers will be 51% (2,640 TWh / 5,138 TWh) and 71% (32,000 TWh / 45,000 TWh). If looking at just the population of people along coastlines, wave energy can potentially fill all of that power demand.

- It’s incredibly technical. Because waves have both an amplitude and period, the capture of their associated kinetic energy requires much more than simply having the waves pass through a turbine. Designs need to transfer the motion of a wave, something that is non-linear in multiple directions, into movement that is linear/unidirectional for a generating system like a turbine, all with energy loss minimized as much as possible. This is very difficult with fluids that move as chaotically as the water in the open ocean. Minute Earth explains it well here.

In addition to the technical challenges of actually capturing the energy, there’s the design challenge of building a device that is resilient against storms, biofouling, and corrosion. A device that is optimized for kinetic energy capture may not be optimized for the occasional violent wave or high wind event. A device that is optimized to do both may have an expensive and impractical maintenance schedule. (Luckily, automation and IoT have helped wave energy converter developers set up systems that respond immediately to potentially disastrous circumstances and alert those onshore of any components that need maintenance.)

All of these engineering challenges need to also be addressed with a design that is cost efficient, further increasing the difficulty. - The combination of the above has created a large ecosystem of creative and diverse wave energy converter designs. The Liquid Grid lists out 130+ different wave energy converters, the vast majority of which are being developed by separate companies. Most fall into seven categories (point adsorbers, terminators, oscillating water columns, attenuators, oscillating wave surge, submerged pressure differential, and rotating mass) but designs can be very different even within each category. For example, though both ExoWave and AW-Energy are classified as oscillating wave surge, one uses moving cones while the other uses a large moving panel. I’ll take some time next week to map out the different wave energy startups with active designs, but for now, know that they are quite diverse in their approaches.

- History has been unkind. Wave energy actually has been around for as long as other renewable technologies like solar and wind, with its first patent tracing back to the late 18th century. Its failure to commercialize as quickly as other technologies can be attributed in part to unfortunate historical dynamics.

First, the competition with wind energy placed pressure on wave to commercialize too quickly during the 1970s oil embargo. Prior to the 1970s, wave energy had actually been on a steady rise. Hundreds of patents had been filed for new wave energy converters throughout the early 20th century and significant advances were made by Yoshio Masuda, the father of modern wave power, in the 1940s and 50s.

The oil embargo of the 1970s spurred a step change in interest in renewables, including wave energy. On the one hand, it incentivized many countries like the UK and Norway and academic institutions like the University of Edinburgh and MIT to start seriously participating in wave energy research. On the other hand, it led to rapid investment in technologies that achieved first commercial, leaving slower-developing technologies behind. For wind, these commercialization milestones were hit in a short period of time. Between the oil embargo in 1973 and the end of high oil prices in the early 1980s, the first US wind farm was put online (1975), the first multi-megawatt turbine was produced (1978), the first commercial wind farm was deployed in New Hampshire (1980), the levelized cost of wind reached $0.38/kWh (1980), several commercial turbine manufacturers were founded (1980 – 1986), and more than a dozen other wind farms were deployed in the US.

For wave, the story played out a big differently. Though exciting developments occurred during this time period, including the invention of famous wave energy converter Salter’s Duck in 1974, the emergence of critical studies for wave energy design, and the establishment of many wave energy-dedicated international conferences in the late 1970s/early 1980s, no technology ever made it beyond the small-scale prototyping stage (even Salter’s Duck). By the mid-1980s, lower and lower oil prices and competing nuclear energy programs led to wave energy programs being shut down and funding being pulled from key technologies. Unfortunately, because wave never hit first commercial, technology development stopped once macro tailwinds disappeared. And because wind had already hit its stride, those that were keen on continuing renewables investment flocked to the winning horse. For wave energy, the window of opportunity vanished before momentum hit.

Wave energy got its second run in the new millennium, but again, market forces led to pre-mature conclusion. 2000 saw the world’s first commercial wave power device in Scotland by a company called Wavegen. This was followed by a number of other key milestones for wave by Pelamis and Aquamarine Power. In 2004, Pelamis tested a full-scale prototype at a wave test site in Scotland and later, in 2008, deployed a 2.25MW commercial farm in Portugal, the first of its kind. Similarly, Aquamarine Power deployed two full-scale prototypes (315kW and 800kW) in 2009 and 2012, respectively. But again, both companies eventually failed because of market timing. Pelamis’ farm was shut down due to technical problems with the generators and lack of funding from the financial crisis to redeploy them. Pelamis later went under in 2014 after failing to acquire more funding (a product of the cleantech 1.0 bust). Aquamarine, despite two successful prototypes and a recently won government award, failed in its 2014/15 raise, resulting in the shutdown of the company. Thus a combination of unfortunate timings around two major macro busts (recession and cleantech 1.0 blowup) cooled down developments in wave energy yet again.

These four characteristics of wave energy – the fact that the market is huge, the problem is hard, the technologies are diverse, and the history is long – make it an interesting case study for other hard tech climatetech spaces, especially those that are going through a similar Cambrian explosion of technology. There are lessons that we can take from looking at this area for not only the future of wave energy development but for the future of other climatetech sectors with a similar profile.

Here's what I observed:

- The wave energy industry depended too much on government funding. One issue with why the first cycle for wave failed was that technologies were dependent on ephemeral wave energy programs set up by governments whose agendas eventually pivoted. While government funding has led the way on development thus far, history shows us that in order to keep this current cycle going, we need investment from private dollars not subject to capricious political budgets.

- The industry was balanced on too few demonstration projects, leading to large losses for the entire industry when those projects went bust. This is especially evident in the second cycle, when wave energy’s renaissance was led by only two major flagship projects: Pelamis and Aquamarine Power. The loss of both of those in a short time period was a huge blow to the wave energy industry. In the future, we need to make sure funding is distributed across many different flagship projects for the overall health of the industry.

The other takeaway from this point is that licensing out the technologies to developing entities can help reduce the risk that a technology will die when a company dies. Perhaps we need to be pushing for more licensing models across R&D-heavy climatetech sectors to better the chances of an industry’s longevity. - Having access to sufficient testing sites with infrastructure that made up the balance of plant was critical for companies being able to iterate their technologies before first commercial. There are more testing sites for wave energy than ever these days, thanks to entities like the Oregon State University, University of New Hampshire, EMEC, The Marine Institute, and many more. But there is still a need for more testing sites, especially ones that can be near potential demand sources for wave energy, like aquaculture, desalination plants, or hydrogen production, in order to properly test load requirements. Going to public or philanthropic sources of funding for these testing sites can be a long journey (PacWave took 10+ years). Is there a way we can incentivize private parties and corporates with pre-permitted sites to offer more testing facilities?

- Revival of old IP is a worthwhile strategy, especially in industries like this that require significant R&D. Long science can sometimes pay off but can also result in lost IP when market forces prevent commercialization. Our technology / VC-heavy ecosystem places a significant premium on new IP, but perhaps it’s worth checking to see what IP may have been unfairly lost in the past and creating an early stage investment ecosystem that supports old IP revival.

- Lack of momentum can have outsized impacts on funding potential. As we saw with wind after the oil embargo, a series of milestones achieved in a short period of time is what allowed it to persist through a competitive oil price environment in the 80s. Lack of that momentum is what led to wave cycle 1’s demise.

There’s a micro and macro lesson here. On an individual company level, demonstrating consistent momentum can make or break your future funding rounds. In practical terms, that means making sure to announce wins – big and small — on a regular basis.

Similarly, on an industry level, demonstrating consistent momentum can lead to more funding and longer support for everyone in the space. That’s why celebrating wins from other companies in the industry, even competitors, can be net positive.

Would love to hear if there are other lessons from those that lived and breathed this cycle or that have seen this play out in other sectors.

Look forward to diving into the wave energy market map next week. Stay tuned!

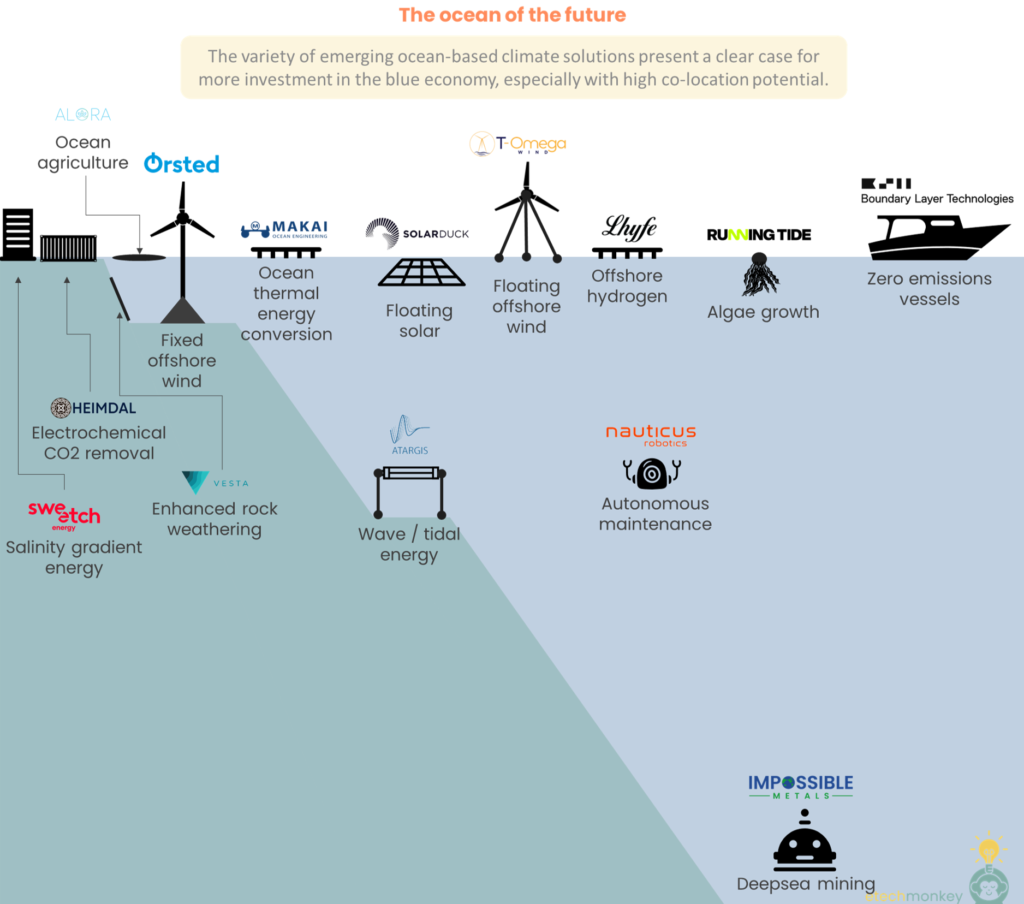

Most of what we talk about in climatetech happens on land – hydrogen production, power generation, carbon sequestration, grid optimization, industrial decarbonization, residential energy efficiency, etc. This is because the majority of technologies get deployed around people’s homes, in city environments, or industrial complexes, all of which largely occur on land.

But what about the ocean?

I became intrigued by the ocean after observing a renaissance of wave energy recently: the DOE announcement on funding for wave energy technologies and a smattering of news for wave energy companies like Atargis, CalWave, Eco Wave, and Mocean.

But wave energy is just one part of a larger suite of ocean-based climate solutions that have emerged over the last few years. The bigger category includes things like tidal energy, mining, regenerative aquaculture, carbon sequestration, low carbon shipping and maritime transport, hydrogen production, offshore solar, and of course, offshore wind.

All of these technologies are in varying stages of development, but most are early stage and require high amounts of capital going forward. Most also face a bevy of challenges being first-of-a-kind in the ocean: long permitting cycles and evolving regulatory requirements, limited testing sites, potential seawater corrosion or storm damage, lack of interconnections, power supply, and other infrastructure, difficult and expensive maintenance, and digital connectivity issues.

Many of these challenges can be tackled with funding, but ocean technologies consistently are deprioritized compared to land-based technologies. Even offshore wind, arguably the golden child for ocean-based technology deployment, is not growing fast enough. Net zero pathways like Princeton’s Net Zero America, BNEF’s Energy Outlook, and John Doerr’s Speed and Scale often build in limited to no allocation for marine solutions outside of offshore wind and ocean protection. Project Drawdown does include additional categories like ocean power, ocean shipping, and improved fisheries, but ranks them all fairly low on the potential impact scale (even offshore wind ranks 38 in a list of 84 ranked solutions, well below its renewables counterparts on land, which take the top 2).

IEA is the only one that seems to give the blue economy some credit. IEA’s ETP list includes 12 different types of overtly (some categories like CO2 storage lump offshore and land-based together) ocean tech and lists the large majority of them as “High” or “Very high” impact (though it’s worth noting that almost 40% of the list of 503 technologies is either “High” or “Very high” impact).

So to summarize, these are early stage technologies that face lots of challenges, require more funding, and are frequently ignored in net zero pathways. What’s the point in putting dollars to work in this area? Why in the world do we need to go through the trouble of funding these ocean-based climate solutions?

Technologies like regenerative / low carbon aquaculture or low carbon shipping are needed to decarbonize industries that we assume will persist in a net zero scenario. So that’s an easy answer.

But for technologies like offshore wind, offshore solar, wave energy, tidal energy, carbon sequestration, seawater and seabed mining, and hydrogen production, there are comparable land-based alternatives that one can argue obviate the need for more complex ocean solutions. A few thoughts on this category:

- The ocean is incredibly resource rich. Seawater provides an abundant feedstock for hydrogen production, minerals extraction, and electrochemical carbon removal. The seabed is also full of critical minerals that can be mined (though there are ecological issues with current methods).

Energy is also more abundant. Wind offshore is stronger and steadier than wind onshore. Wave energy is 5-10x more energy dense than wind or solar. There’s even evidence to suggest that offshore solar is more efficient than solar on land.

With the concentration of resources and energy across a wider surface area, the ocean can provide a similar profile of climate solutions as on land across a smaller footprint.

- As populations tend to be coastal, the ocean can solve the climatetech NIMBY problem. Roughly 40% of the population in the US and across the world live in coastal areas, meaning that a good portion of the energy demand is actually close to ocean-based power. Building power generation out in the ocean can provide sufficient electricity for that portion of the population while also staying far away enough from arable land and communities to avoid the NIMBYism that plagues most other land-based climatetech solutions.

Energy potential is not a bottleneck here either. Ocean-based power can fulfill the US’ and world’s current electricity needs 4 - 19x over (US offshore wind potential: 13,500 TWh + US wave energy potential: 2,640 TWh = >4x current US electricity consumption; world offshore wind potential: 420,000 TWh + world wave energy potential: 32,000 TWh = >19x current world electricity consumption).

- High co-location potential in the ocean can create dense carbon reduction areas that minimize infrastructure requirements and impacts to the broader ocean. The nice thing about ocean climate solutions is that, with easier subsurface access, they can stack nicely with each other. While co-located offshore wind and solar can take advantage of surface-level energy, wave and tidal power can harness energy from below. At the same time, nearby platforms and assets can be used for hydrogen production, aquaculture, carbon sequestration, or even seawater mining. One can imagine these “ocean centers” spread across coastlines, allowing multiple projects to take advantage of the same supply/offtake lines or maintenance routes. Co-locating intermittent renewable energy from wind/solar with more steady power from waves can also smooth out the duck curve, reduce capex needs, and increase energy security (especially for island nations).

Co-location studies for ocean climate solutions are well underway (offshore wind with wave power, offshore wind with tidal power, and aquaculture with ocean power) and several multi-use platforms have already been trialed/built. Although regulatory hurdles and the capital/complexity requirements of a larger project may be initially awkward to navigate for pioneering co-location projects, the potential synergies from co-location will hopefully move funding in this direction.

TLDR; ocean-based climate solutions present a valuable but underappreciated solution set to the world’s climate challenges. The ocean’s plentiful resources, proximity to demand centers, and high co-location potential present a compelling opportunity for both builders and investors in climatetech.

Companies shown: Sweetch Energy, Heimdal, Alora, Orsted, Makai, Atargis, SolarDuck, T-Omega, Lhyfe, Nauticus Robotics, Running Tide, Boundary Layer Technologies, Impossible Metals

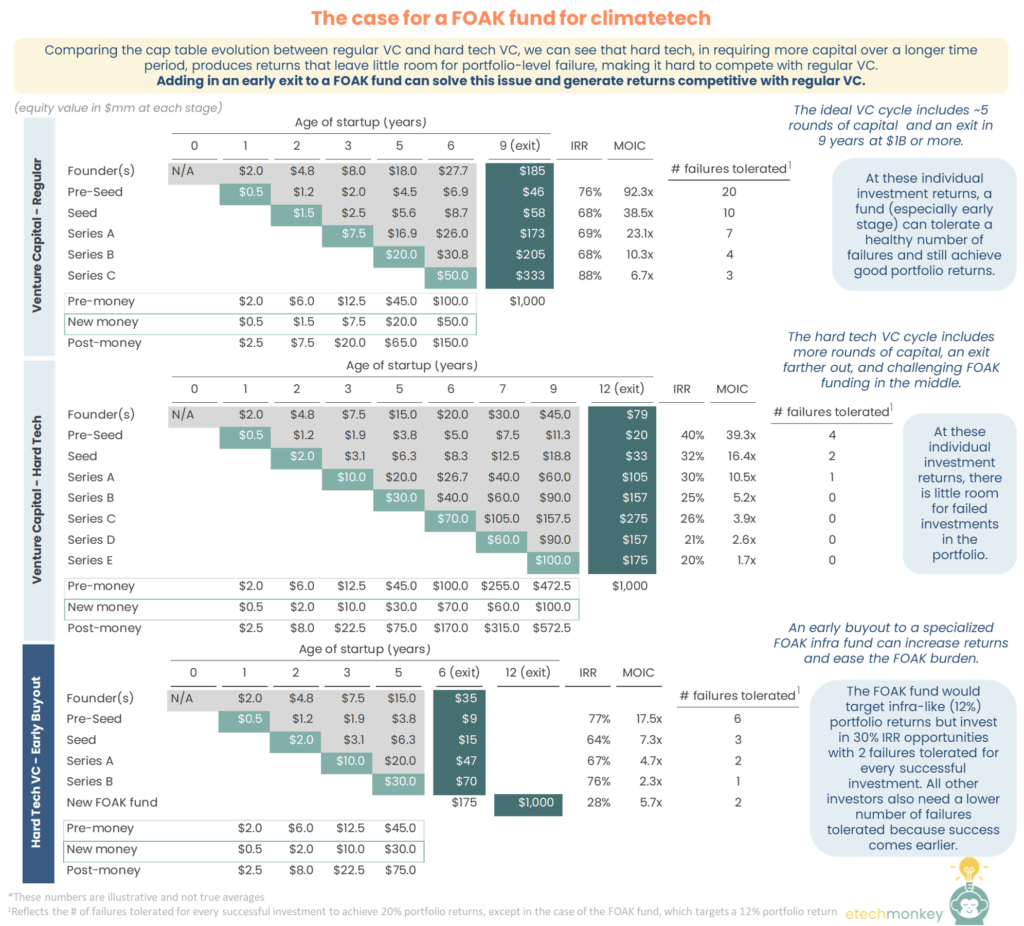

This week I had a grand plan to write about the economics of first commercial facility / FOAK commercial and why it makes complete sense to invest in these projects. But it was much more difficult to make the numbers work than anticipated. Even if a company gets over the FOAK hurdle, the lengthy time to exit coupled with the higher capital need results in returns for venture investors far from competitive to regular way venture investments.

There are paths to achieving competitive returns to regular VC – some existing ways include having philanthropic or government capital come in at FOAK stage, which can ‘lever’ up a project with non-dilutive financing, pursuing a licensing model, which, with the right partner, can allow a company to scale faster with less capital requirements, or recruiting an evergreen fund or fund-like operating entity that can provide flexible financing at multiple stages to accelerate the scale up.

But the path that is most murky (or at least was to me when I decided on this topic) is how to achieve competitive returns with a traditional institutional capital cycle.

After experimenting with a rough model, I found that one way you can achieve competitive returns is by creating a FOAK-focused fund and encouraging companies to early exit to this fund. The early exit helps early stage venture investors find liquidity sooner, increasing IRRs and the likelihood of a successful investment. For the FOAK-focused fund, acquiring the company before FOAK means having the ability to capture all future facility economics vs. competing for 2nd facility and beyond economics with very low cost of capital. The likely levered returns past first facility substantially reward the FOAK investor for taking the FOAK risk.

This FOAK fund is not unlike a private equity firm that aims to acquire a company and lever it up before exiting in a few years. The difference is that this FOAK fund would aim for infra-like returns (10 - 15%, or the higher end of infra) at the portfolio level and private equity-like returns (20 - 30%) at the individual investment level, building in some expected failure rate (in the example below, 2 out of 3 investments can fail and the portfolio will be fine) similar to a venture fund to go from the individual investment to portfolio level returns.

The FOAK fund is a novel concept because 1) infra investors are generally extremely risk averse and don’t think about their portfolio in failure terms, 2) private equity investors do balance their portfolio according to expected return but also don’t necessarily build in a failure rate and don’t aim for as modest of a portfolio return, and 3) venture investors do think about failure rate but don’t typically look for opportunities to optimize for cash flow or lever up an investment. A vehicle that combines elements of private equity, infrastructure, and venture capital can address the imperfect match of each one of these traditional vehicles with the FOAK problem.

I don’t think there is something out there in the market today that looks like this…the closest is Generate Capital and their strategy of acquiring, operating, and scaling sustainable infrastructure companies. But I haven’t seen an institutional investor that addresses the FOAK problem. Perhaps someone can correct me here!

Here’s how the returns stack up in this illustrative example:

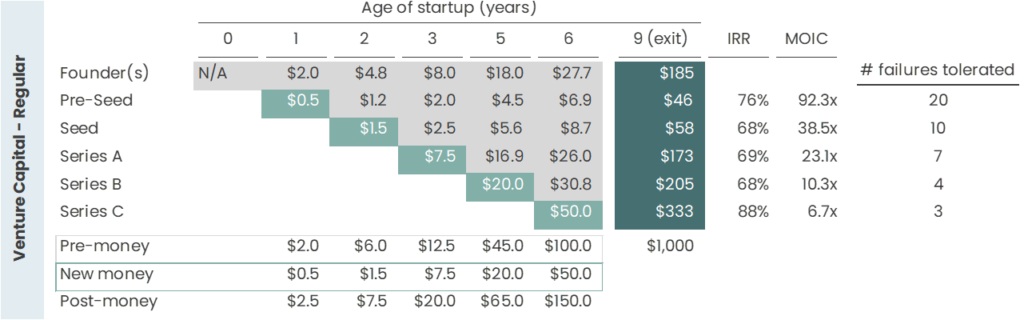

A typical venture cycle runs 4 - 5 rounds of funding before a company exit. Because of the high failure rate of startups, VC investors target a homerun exit – $1B or more in less than 10 years. Putting in some reasonable assumptions for round sizes and valuations up until that point, we get that, for this individual investment, a Pre-Seed investor can expect a return of 76% IRR / 92x MOIC, a Seed investor can expect a 68% IRR / 39x MOIC, a Series A investor can expect a 69% IRR / 23x MOIC, a Series B investor can expect a 68% IRR / 10x MOIC, and a Series C investor can expect an 88% IRR / 6.7x MOIC.

If we assume these returns for the successful homerun investment, that means that, in order to achieve a minimum of 20% portfolio IRRs, a Pre-Seed investor can have 20 failures to one successful investment, a Seed investor can have 10 failures, a Series A investor can have 7 failures, a Series B investor can have 4 failures, and finally a Series C investor has the least amount of wiggle room with 3 failures.

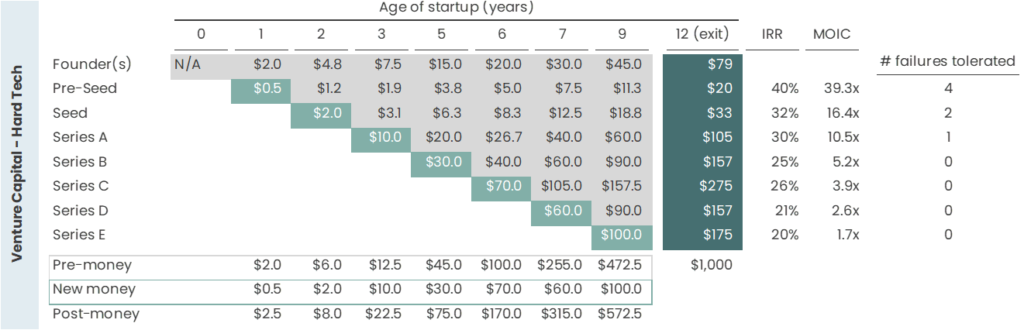

Moving on to the hard tech example, we assume that the round sizes increase due to greater capital intensity, two more rounds of capital are added to fund additional development, and exit gets prolonged 3 years until the 12th year of the startup’s existence. In this case, the returns are lowered to 40% / 39x for a Pre-Seed, 32% / 16x for seed, 30% / 10x for Series A, 25% / 5.2x for Series B, and 26% / 3.9x for Series C. Series D and E investors get a 20 – 21% or 1.7 – 2.6x return. The failure tolerances are significantly decreased, with Pre-Seed investors only allowed 4 failures to maintain a 20% portfolio return, Seed investors 2 failures, Series A investors 1 failure, and all other later stage investors no failures (i.e. every investment must be a success, a tall order for this type of risk capital).

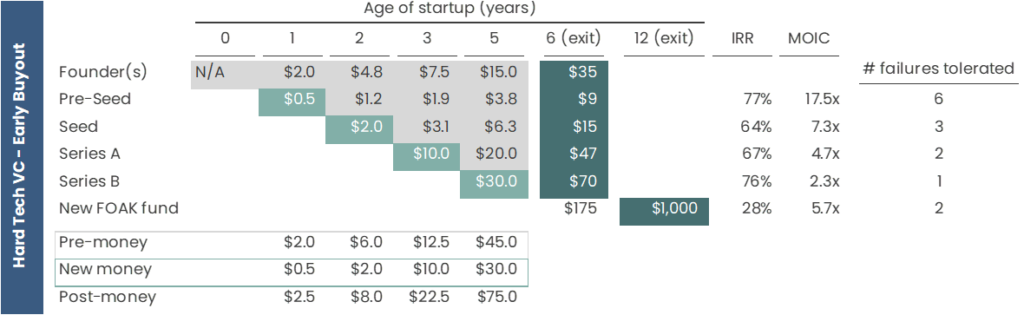

Now we come onto the early exit case. In this scenario, the company raises a few rounds of capital to develop the technology to the point where it’s ready for FOAK commercial. Then, the company exits early to a FOAK fund. The FOAK fund acquires the company at a lower discount rate than what the VC investors would normally target, therefore being able to pay more than what a VC would have valued the company. After the FOAK fund acquires the company, it helps the company get past FOAK and move onto being a levered fully functioning infrastructure owner-operator, after which it can be exited.

Exiting early allows the Pre-Seed investors to realize a 77% / 18x return, the Seed investors a 64% / 7.3x return, the Series A investors a 67% / 4.7x return, and the Series B investors a 76% / 2.3x return. Though the MOIC is lower, the IRRs compare since the capital is returned a lot sooner. Exiting early also allows for a lower failure threshold, since the liquidity event for these investors is no longer dependent on getting past FOAK. Thus the 6 failures for Pre-Seed, 3 for Seed, 2 for Series A, and 1 for Series B, while lower than in traditional VC, reflect an easier success case.

For the FOAK fund investor that invested with a premium valuation to a VC, they would still be able to realize an exit at nearly 30% IRR and 5.7x MOIC, a very healthy return for any private equity or infrastructure investment. Because this investor is taking FOAK risk, there is a chance that the investment fails in a binary fashion (vs. half-failing or generating a partial return), similar to a VC investment. In this case, with a 28% individual investment return, the FOAK fund investor can tolerate a reasonable 2 failures for every success case to achieve a “risky infra” return of 12%.

TLDR;

Investors, new or existing in climatetech, can create a functioning FOAK strategy that can make investing in FOAK a financially attractive proposition.

Founders in hard tech climatetech can look to early exits as a means of scaling and providing liquidity to early investors. Also early exits to risk-taking infra investors can be more lucrative than continuing with the venture cycle.

Service providers can consider encouraging and supporting the creation of these FOAK funds.

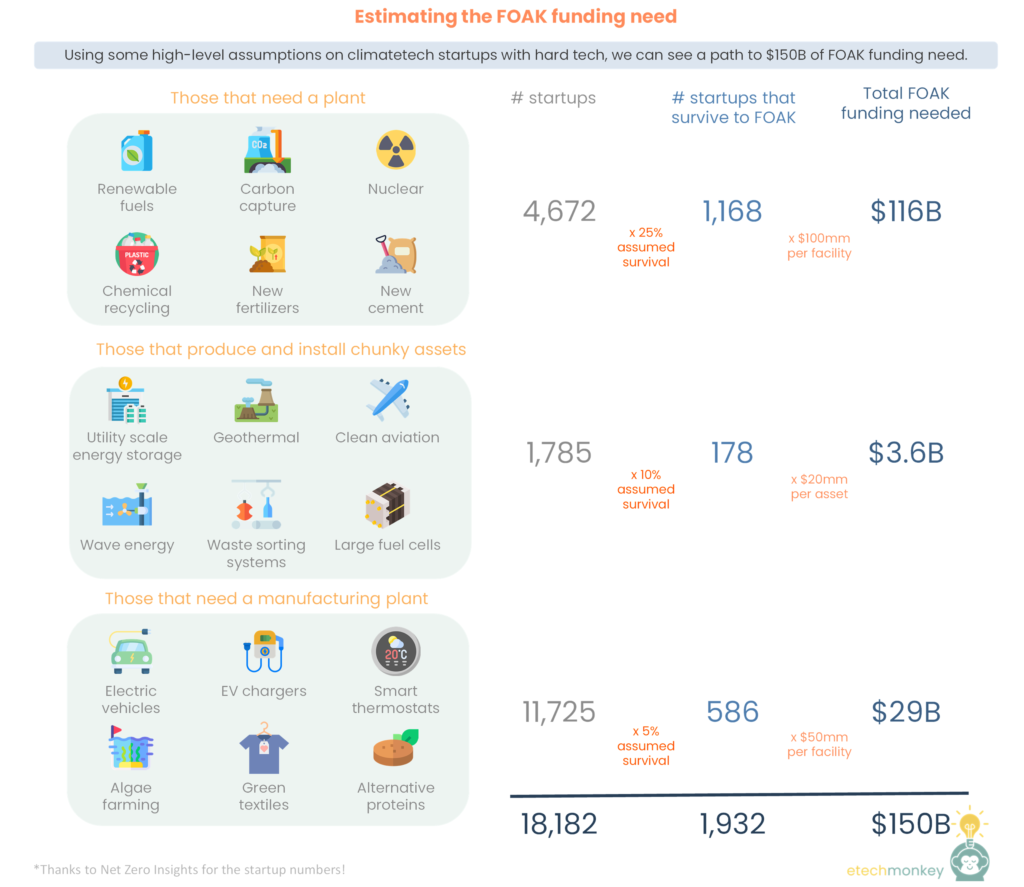

After discussing types of FOAK last week, this week I wanted to see if I could find a good estimate for the amount of FOAK funding we need.

One way to look at this is to try to pare down estimated infrastructure spend to what will be spent on FOAK technologies.

Most infra spend estimates land at ~$4 to $9 trillion / year. These numbers are never detailed enough to understand specific technologies they’re actually building in, but we can kind of glean from the breakouts an upper-end limit for what spend might be:

- IEA estimates ~$4.5 - 5 trillion / year spend. $630 billion of this (~14%) will be from CCUS and hydrogen, both technologies that will likely need either large assets or large plants. Another $832 billion (another 18%) will come from batteries, another area that is far from being commercially mature. Add in new bioenergies, low carbon industrial processes, and non-wind/solar/hydro renewables and total infra spending from technologies not yet scaled could be 45% of 2050 investment or $2T. (As a sanity check, IEA also estimates that 45% of the emissions reduction that’s needed by 2050 comes from technologies not yet past demo stage, so this number is pretty consistent with that.)

- GFANZ estimates a $4.5 trillion / year spend. They don’t break it down by technology as nicely as IEA does but their end us sectors are similar: adding together the $359mm on industry decarbonization, $218mm on low emissions fuels, $161mm on ag/food, and a fraction (I use 30%) of the $3T they estimate will be used for electricity and transport, ~36% or $1.6T can be from technologies not yet scaled.

- McKinsey estimates a $9.2 trillion / year average annual spend by 2050. $4.5 trillion (~49%) of this is on low emissions assets. I’ve estimated using their sector breakdown and their low emissions asset spend number that this $4.5 trillion includes: $1.2T on new mobility and power, $100B from new industry, $280B from new ag/food, and $200B from new hydrogen/biofuels/heat. This totals to ~$1.8T spent on new technologies.

So all of the estimates roughly point to $1.5 - 2T / year being spent on technologies that have not yet scaled. Over the next 28 years, that’s $42 – 56T in total. Let’s just call it $50T as a midpoint.

To estimate how much we’d need for FOAK, we can just ballpark how much funding we can assign to deployed facilities (2nd facility and beyond) for every FOAK – or, assuming FOAK cost is around the commercial cost, basically how many deployed facilities for every FOAK facility. As one bookend, we can say that 1 out of every 100 facilities requires a FOAK. This is very high level but not crazy to assume. There are only 109 biodiesel plants in the US, 31 years after the first biodiesel plant in Kansas. There are only 18 renewable diesel plants (5 - 6 current renewable diesel plants with another 12 under construction), 12 years after the first renewable diesel plant in Louisiana. Using 1/100, that means we’d need to spend $500B for FOAK assets.

Another bookend would be looking at solar farms as a comp. There are 2,500 solar farms in the US, 39 years after the first solar farm in California. Let’s assume there’s 4 different types of PV (monocrystalline, polycrystalline, multijunction, and thin film) and that these 2,500 only needed 4 FOAKs (probably a very wrong assumption). If we assume 4 out of every 2,500 facilities requires a FOAK, we’d need $80B for FOAK assets.

So somewhere between $80B - $500B is probably the right number here…

To put this into context, PE funding in cleantech is at around $20 – 25B / year, while late stage VC funding is at ~$24B / year. If all of this funding was directed towards FOAK, we’d have enough…but part of this funding is used for digital technologies and for stages other than FOAK. If we assume that we have to put all of the FOAK in place by the halfway mark, we only really have $700B in place for potential FOAK funding. At the low end, 11% of our late stage – PE capital should be directed to FOAK. At the high end, 70% of that capital should be directed to FOAK.

I can tell you anecdotally that that true percentage of capital being directed to FOAK is nowhere near 11%, much less 70%.

If you’re not convinced by this top-down method of estimating potential FOAK spend, we can try to do a bottoms-up approach. We can assume that each startup that survives to FOAK needs FOAK funding…so we need an estimate the number of climatetech startups that are out there that will survive to FOAK.

Using Net Zero Insights’ database, I isolated 32 key areas that will likely need chunky FOAK funding, separated by the approximate types they’ll be in:

- Large plants: DAC, CCUS, sustainable aviation fuels, nuclear, steel, alternative proteins, water treatment, cement, biofuels, hydrogen, recycling, chemical, petchem/plastic

- Large assets: aviation, CSP, geothermal, wave, hydro, offshore, energy generation, energy storage

- Large manufacturing factories: aquaculture, algae, maritime, textiles, EVs, micromobility, PVs, robotics, energy efficiency, built environment, and food/ag

18,182 startups were identified as being in these categories. Let’s assume that 25% of the large plants, 10% of large assets, and 5% of large manufacturing faciltiies make it to FOAK. At $100mm per FOAK, that would mean we need $193B in funding for FOAK with just the startups that exist today. If we attempt to get more granular on individual category funding needs and assume the large plants need an average of $100mm, assets need $20mm, and manufacturing facilities need $50mm, we get $150B. At $150 – 193B of FOAK need, we’d need 21 - 28% of late stage VC + PE capital directed to FOAK, implying that one out of every 4 of these late stage deals need to be funding a FOAK.

I realize that a lot of this exercise is very hand-wavey…but it does at a high level illustrate an important need to direct more funding to FOAK facilities. We either need to be deliberately setting targets for the proportion of institutional deals that are FOAK OR we need to be bringing more capital in the door to help fund FOAK. In that latter case, the government, non-profits, and non-traditional capital sources like family offices and sovereign wealth funds will play an important role.

TLDR; FOAK funding will cost us billions, likely hundreds of billions, of dollars. We need more funding directed to it.